Abstract

Whilst many introduced non-native plants and animals become naturalised or even invasive, others fail to persist. Golden Pheasants (Chrysolophus pictus) have occurred in multiple regions outside of their native China, with the largest populations establishing in the United Kingdom. Now very rare in the UK, ongoing releases make its continued ‘wild’ status dubious. The Golden Pheasant in Britain provides a case study of an introduced species that at first appeared to thrive before declining to the point where no viable wild populations remain. Here, we outline the history of Britain’s Golden Pheasants before describing their current status. To do so, we reviewed the relevant literature, engaged in personal communications with rural staff and birdwatchers, and carried out a survey of a putative remnant population. We conclude that there are 37–40 ‘wild’ Golden Pheasants left in the UK, within two regions (both populations are dependent on human management via supplementary releases, food provision, or predator control, and therefore can no longer be considered to be truly naturalised as of 2023). This represents a significant decline from a 1993 UK population of 1000–2000. There is no evidence to suggest that Golden Pheasants persist in the UK as a self-sustaining population in 2023. We use this case study to discuss the issues associated with determining whether non-native populations are viable in the long term, and situations where apparently successful colonists then decline to extinction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Whilst many non-native species are a threat to global biodiversity, contributing to the loss of native species, other populations struggle to establish or persist in their new environment. Such species can still have economic and environmental impacts. For example, the Black Rat Rattus rattus was common in Britain as an urban pest, but declined since the eighteenth century and is now very rare (Twigg 1992). Determining which species will succeed as introductions is vital in predicting their impacts on ecosystems, and therefore initiating a conservation response. One area of focus is assessing whether populations become ‘self-sustaining’ or ‘naturalised’ (i.e., form populations that can persist without supplementation from escapes or releases). This can be difficult to resolve, especially in situations where ongoing introductions are common (McInerny et al. 2022a). In many situations, introduced populations can appear to naturalise but then decline to extinction (Jeschke 2014). Our understanding of the biology of such cases is often limited.

The Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus is one of two species in the genus Chrysolophus, along with the Lady Amherst’s Pheasant C. amherstiae, which also had a small naturalised population in Britain in the twentieth century. Golden Pheasants are endemic to China, where little is known of their lives in the wild (Balmer et al. 1996). In captivity, the species is a common aviary bird, and is also kept in a free-roaming decorative context. Escapes and releases formed wild populations, which have occurred around the world (Lever 2010). The only non-native populations which were widely considered to be ‘naturalised’ (i.e., self-sustaining) were those of Breckland in England, and perhaps Galloway Forest Park in Scotland (Balmer et al. 1996). The Golden Pheasant was added to the British List (of wild birds) in 1971 (Balmer et al. 1996; McInerny et al. 2022b). Whilst the Golden Pheasant has been retained on the British List’s Category C as a ‘naturalised introduction’, the Lady Amherst’s Pheasant was moved to Category C6 (‘former introduced breeders’) in 2005 (Dudley 2005). Although Lady Amherst’s Pheasants are still occasionally seen ‘in the wild’ in Britain following escapes or releases [e.g., a male was observed in December 2022 at Flitwick, Bedfordshire, England (eBird 2022)], no descendants of the original ‘self-sustaining’ population remain. With respect to the Golden Pheasant, it is now unclear whether any ‘wild’ individuals persist (i.e., birds which are part of, or descend from, a longstanding population that putatively is, or was, claimed to be self-sustaining/naturalised), as opposed to free-roaming decorative birds (those released for ornamental purposes in private and public gardens, which are usually unafraid of proximity to humans and can even be tame), other releases (e.g., birds deliberately released by shooting estates for interest, or to try to establish ‘wild’ populations), escapes (birds which were not deliberately released but have been lost from captivity), or the offspring of such birds.

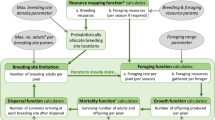

In this paper we outline the changing status of Britain’s Golden Pheasants, via a literature review plus personal communications with birdwatchers and rural staff at relevant locations. When these communications relate to private land, or to ongoing illegal releases, individuals are kept anonymous. We also report on a trapping survey carried out in 2022 and 2023 on a putative remnant population within the prior British stronghold of Breckland, where we aimed to confirm their persistence, estimate their population size, and identify any immature birds. This would highlight ongoing breeding or releases. In light of our results, we discuss the species’ prospects in Britain, and outline the importance of predicting colonisation success of introduced populations more generally.

Main

The history of Golden Pheasants in the UK

There has, until now, been no single treatment of the Golden Pheasant’s history in the UK. Here we outline the introduction, distribution and decline of this elusive forest-dwelling species, as presented in various sources.

1800–1900

The first ‘free-roaming’ Golden Pheasant in Britain was recorded in Norfolk in 1845, but deliberate and sustained releases did not occur until the turn of the century (Brown and Grice 2005). During the nineteenth century, there were early failed attempts to naturalise the species in the Scottish Highlands and the Isle of Gigha, followed by successful introduction to Breckland, which was to become the species’ British stronghold, in the late 1880s (Taylor and Marchant 2011).

1900–1981

During the early twentieth century, there was an increase in Golden Pheasant releases around the country (Table 1, Fig. 1A). Birds were found in conifer plantations (especially 15–30 years after planting) or woodlands with a Rhododendron understory (Balmer et al. 1996). There were only two regions where substantial populations could be found—in Breckland (Brown and Grice 2005), England, where certain locations held up to 100 birds in the 1950s and 60s, and in Galloway Forest Park, Scotland, where there were estimated to be 250 individuals in 1974 (Thom 2010). Many, if not all, British Golden Pheasant populations exhibited at least some phenotypic signs of hybridisation with Lady Amherst’s Pheasants. The most common traits of birds with hybrid ancestry are a black throat and a pale rather than orange-yellow cape (Peng et al. 2016)—although these traits may also occur as natural mutations in pure Golden Pheasants—genomic research is required. Smaller, more ephemeral populations were also founded. In north Norfolk, England (around Wolferton—Fig. 1B), birds were introduced around 1967 (Taylor and Marchant 2011). In the South Downs, England (Wearing 2011), birds colonised between 1968 and 1991, and up to 22 males were present at one site in 1987 (Brown and Grice 2005). In Anglesey, Wales, birds were introduced in the 1960s, and 30–35 were present in 1994 (Lovegrove et al. 1994). Golden Pheasants were introduced to Poole Harbour, England, in the 1920s, and a population of 10–25 pairs was, in 2005, said to have been ‘long-established’ (Sharrock 1976; Birds of Poole Harbour 2020).

A A map showing sites known for Golden Pheasants in Britain, and their 2022 status at each location. B The presumed final Golden Pheasant of the North Norfolk population—at Wolferton (in 2012). This adult male was often seen by the side of the road adjacent to a region of Rhododendron. (Credit: Alastair Stevenson). C Free-roaming Golden Pheasants in Tresco Abbey Gardens, Isles of Scilly. These birds rarely breed, and most individuals were hatched in captivity (Credit: Joe Woodman)

Post 1981 declines and extinctions

Releasing the species became illegal in 1981 with the introduction of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (Balmer et al. 1996). After this, the number of Golden Pheasants across all sites either continued to decline, or began to decline. In Anglesey, the species was probably extinct by the year 2000 (pers. comm. Stephen Culley). With respect to the South Downs, after 2000 (excluding a short-lived group of up to 30 birds next to a keeper’s cottage near Lewes) only single individuals or pairs were seen even at the previous strongholds of Kingley Vale and West Dean Woods, and the Golden Pheasant quickly went extinct in the region (Thomas 2014; Eyre 2015; Wearing 2011). Galloway’s population also declined to ten birds in 1993, and had disappeared by the twenty-first century (Balmer et al. 1996; Thom 2010). The northwest Norfolk population appears to have gone extinct by 2018, with no sightings reported since that year on either eBird or BirdTrack, or in the annual reports of the Rare Breeding Birds Panel. Excluding free-ranging decorative birds, this left Breckland and Poole Harbour as the two regions remaining, past 2020, which might hold ‘naturalised’ populations, or birds descending from populations that were once naturalised. The report on non-native breeding birds in the UK in 2012–2014 described the prospects of the Golden Pheasants persistence as being ‘unclear’ (Holling et al. 2017).

Free-roaming decorative Golden Pheasants

There are several locations in the UK, including Tresco on the Isles of Scilly (Fig. 1C), Abbotsbury Subtropical Gardens, and Kew Gardens (Fig. 1A), where small numbers of free-roaming Golden Pheasants can be seen. Golden Pheasants have also been seen recently at Strathdearn, Highland, where many individuals have plastic/avicultural leg rings (and therefore are obvious recent illegal releases), and Lady Amherst’s Pheasants are also reported (Joss et al. 2020, 2021). Successful breeding does not occur in such places often, and almost all birds are of captive origin (pers. comm, anonymous). On Tresco, where Golden Pheasants are tame (unlike their Breckland conspecifics), new birds are released roughly every decade, and recent releases included Lady Amherst’s Pheasants (pers. comm. anonymous).

Status in 2022/2023

Establishing wild or captive provenance of birds reported in Breckland or Poole Harbour is now challenging. There is one Breckland site, henceforth known as Site A given sensitivities around private land, where up to 25 Golden Pheasants are claimed to be present. The 2020 Rare Breeding Bird Report stated that it is home to a ‘stable’ population of around 20 individuals (Eaton et al. 2022). Staff at the site have stated that the only release in the past 20 years was four ‘yellow’ Golden Pheasants (a morph bred in captivity) around 2011–2014 (pers. comm. anonymous). It seems that the yellow birds died by 2023 without breeding. A conflicting report claims that the persistence of Golden Pheasants at Site A is due to semi-regular (illegal) releases (pers. comm. anonymous). Additionally, a Reeve’s Pheasant Syrmaticus reevesii, which is also not native to the UK, has been seen, indicating a willingness among certain individuals in the vicinity to release exotic species (pers. obs., DEB).

Elsewhere in Breckland, as of 2023, there is no evidence of wild Golden Pheasants persisting. Small numbers of Golden Pheasants were sighted until recently in a private location, with photographic evidence from 2016 and 2019 but no later (pers. comm. Richard Moores). At a third location, east of Thetford, a roadkill second-year male was found in 2022. Finally, there have been reports of single individuals, almost certainly escapees from captivity, at disparate sites. Since 2018, these include Santon Downham, Nunnery Lakes, Mildenhall Woods, Narborough, and King Row (near Shipdham) (BirdTrack 2022; eBird 2022; Stoddart 2022). There is therefore no evidence suggesting that, as of 2022, there are more than a couple of individuals at any location in Breckland, excluding Site A. Depending on the extent to which recruitment into that population is due to wild breeding or new releases, some of its Golden Pheasants may have an ancestry component derived from the original ‘naturalised’ population.

As of 2022, the only wild Golden Pheasant population in the UK outside of Breckland is that of the Poole Harbour islands. This population is supported by regular releases and food provision (pers. comm. Paul Morton). The presence of recently released Lady Amherst’s Pheasants and Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus, and tameness of many of the Golden Pheasant individuals, provides further evidence that the Poole Harbour ‘population’ is heavily dependent on human management. The Brownsea Island population is now nearly extinct, with only one bird located during a 2020 survey. Furzey Island, Green Island, and Round Island were found to be home to 16, 12 and 4 birds respectively (Birds of Poole Harbour 2020).

A putative remnant Golden Pheasant population in Breckland

Of the two regions in Britain which could be home to either ‘naturalised’ Golden Pheasants or Golden Pheasants which descend from a population that was once naturalised, the Poole Harbour population appears to be more directly sustained by released individuals. At Site A, the extent to which birds descend from the original ‘wild’ Breckland population, or to recently released birds, is unclear. Site A is an area of mixed woodland within farmland (Fig. 2A). The 2017, 2018 and 2019 Rare Breeding Bird Reports did not report proof of breeding (Eaton et al. 2021; Holling et al. 2020, 2019), although breeding is now known to have happened in 2018 (pers. comm. anonymous). The 2020 Rare Breeding Bird Report recorded two broods (Eaton et al. 2022). Whilst young chicks have been seen, immature birds have become increasingly rare despite intense predator control (pers. comm. anonymous). The population is vulnerable to disturbance from trespassing birdwatchers, which has resulted in at least two birds being flushed into oncoming traffic in recent years (pers. comm. anonymous).

A The habitat at Site A consists of areas of Rhododendron thicket in an area of mixed woodland. Four individual Golden Pheasants were caught in this habitat during the 2022 and 2023 surveys, and resighted with camera traps. B Individual 1, ringed in 2022 and resighted with camera traps visiting a deactivated live-trap in 2023, is an adult male with a pale cape (usual cape colour is yellow-orange). C Individual 2 was a second year when first ringed in 2022, and in its full adult plumage in 2023 when it was recaptured. D Individual 3, ringed in 2023, was another adult male with a yellow cape, but had a darker face than Individual 2, enabling them to be distinguished in camera trap footage. E Individual 4, ringed in 2023, was an adult female

We carried out a survey at Site A in 2022 and 2023, to confirm the presence of Golden Pheasants, assess whether population size estimates of 20–25 are accurate, and to explore whether population recruitment (either breeding or releases) still happens. After two pilot visits (February 26th 2022 at 9:30–11:30 am, and 11th June 2022 at 8:00–11:30 am), resulting in one sighting of an adult male Golden Pheasant, we carried out a live-trapping survey. We worked from the 25th to the 28th of June and from the 2nd to the 4th of July, using five cage traps baited with seed. We caught two birds. These were an adult male (Fig. 2B) and a second-year male, both undergoing moult. Birds were fitted with British Trust for Ornithology metal identifying leg rings, measured, weighed, and released. It is not possible to determine whether the subadult pheasant we captured hatched in an aviary or in the wild. Nevertheless, combined with the dead subadult bird found in the site east of Thetford in 2022, and observations made at Site A in 2020, this suggests that there are either Golden Pheasants still breeding in the wild in Breckland, or that there are ongoing releases as of 2021. Following on from this, we repeated our live-trapping survey in January and February 2023, with ten cage traps. Traps were left in place (de-activated so that accidental capture was not possible) to habituate the pheasants on the 14th January (two adult male Golden Pheasants were seen), and then trapping was carried out on January 21st, January 28th, February 4th, and February 11th. Traps were moved around the suitable area of habitat within Site A. We also used two camera traps (Bushnell, Kansas, United States), which we used to identify whether any unringed birds were present. We captured one retrap bird on January 28th (Fig. 2C—the bird ringed in 2022 as a second-year) and two new birds on February 11th (an adult male (Fig. 2D) and an adult female (Fig. 2E)). We also saw the other individual which had been ringed in 2022 (recognisable due to a pale rather than yellow cape, probably due to a degree of Lady Amherst’s Pheasant ancestry). Camera trapping from the 11th to the 18th of February showed all four known individuals (each bird was seen multiple times) and no unringed individuals, suggesting that all or almost all birds in the population had been caught (meaning that the Site A population is likely to be 4–7 birds rather than 20–25 as claimed previously). None of the four birds known to live at Site A in January/February 2023 are known second-year birds. A male (the individual with a pale cape) was seen displaying to the female on a camera trap on the 9th February at 08:34 am. With regards to potential predators, no Red Foxes Vulpes vulpes were seen in the entire four weeks of camera trapping. At least two domestic cats, which could pose a particular risk to any Golden Pheasant chicks, were seen.

National population estimate and future prospects

The national ‘wild’ population of Golden Pheasants in 2023 is restricted to Breckland plus the Poole Harbour Islands. Seeing as the Poole Harbour population was surveyed as 33 in 2020 and Site A has 4–7 individuals, the national population in 2023 is likely to be between 37 and 40 individuals, a significant proportion of which will have been hatched in captivity. A stricter interpretation of the term ‘wild’, which would discount the Poole Harbour birds due to the tameness of some individuals and the evidence that active supplementation via releases has been more regular (and more necessary to maintain a Golden Pheasant presence over the years) than at Site A, would mean that the national wild population would only include the birds present at Site A (i.e., it would be 4–7). The UK’s 1993 Golden Pheasant population was estimated as 1000–2000 individuals (Gibbons et al. 1993). There are no populations left today which have not, to some extent, been supplemented by (illegal) releases in the past decade.

Britain’s ‘wild’ Golden Pheasants persist thanks to predator control, feeding, prevention of public access, and supplementation with captive-bred birds. Even in Breckland, the population failed to sustain itself for more than a few decades post-1981. It is almost certain that no free-living Golden Pheasants in the UK have unbroken wild ancestry since the population was declared to be ‘naturalised’ in 1971, and it is possible that some, or even most, of the remaining ‘wild’ birds (including at Site A) were actually hatched in captivity. If the Site A population appears to expand in the future then this will almost certainly signify a new release regime. Given that the population has dwindled over the past two decades even with intense predator control, no apparent habitat change, and with supplementary winter feeding, there is limited capacity for a ‘natural’ population increase. Following a more developed rubric and definition of the term ‘self-sustaining’ (McInerny et al. 2022a), the Golden Pheasant should be moved to Category C6 as a ‘formerly self-sustaining’ introduced species in the UK (i.e., it is now extinct in a naturalised sense).

Discussion

Factors influencing the post-1981 decline

It seems likely that the primary reason for the decline of the Golden Pheasant has been a simple decline in the numbers of released birds since 1981. The Lady Amherst’s Pheasant’s extinction was accelerated by habitat change (Nightingale 2005) and, given that we have already mentioned the specific habitat requirements of Golden Pheasants, there is cause to suspect similar reasons (Rhododendron clearance, maturation of plantations) as underlying the failure of released birds to maintain populations in the long term. It is also worth outlining the role of predation, which may have increased following a reduction in the intensity of persecution of many species on shooting estates. Of five Golden Pheasants radio-tracked in the 1990s, three were killed by Red Foxes within about a year of capture (Balmer et al. 1996). It is worth noting that across all known sites, females have been less commonly observed than males. It could be that the cryptic females are more difficult to see (Fig. 3A), or are less likely to be released. Importantly though, it might be that females are predated whilst brooding eggs. There is probably an interaction between habitat and predation, whereby denser forest growth phases allow pheasants to avoid predation more easily. As well as this, although the Breckland population consisted of several hundred birds (Balmer et al. 1996; Taylor et al. 1999), it is not clear how connected different sites ever were in terms of gene flow among populations. It is known that the birds do not move far when adults, and juvenile dispersal distances might also be assumed to be low, particularly across unsuitable habitat in a fragmented landscape. The Breckland ‘self-sustaining population’ was likely, for much of its history, multiple small populations, sustained by sporadic release events. If this was true, the Breckland Golden Pheasants would have had a low effective population size. Nevertheless, it is possible that at least some populations would have maintained themselves without supplementation had vegetative change and changing predation regimes not occurred.

Relevance to the study of introduced and invasive species

Britain’s Golden Pheasants represent an interesting case study of an introduced species. Following a period where the population appeared to thrive, a subsequent decline has doomed the species to extinction as a wild bird in the UK. The majority of introduced species fail to form naturalised populations (Jeschke 2014). The Golden Pheasant’s apparent success followed by failure raises interesting questions about whether it was ever truly self-sustaining. Such concerns are relevant for varying reasons. First, introductions of certain species are so frequent that it is unclear what role the species would play in the ecosystem if the introduction regime changed. For example, the Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus and Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa are, in much of their UK ‘range’, sustained by annual releases of millions of birds (Blackburn and Gaston 2021). It is not clear whether they would exist in many areas if such releases ceased. This is important as, depending on the time of year, 25–50% of the UK’s avian biomass is made up of these two species (which will clearly have enormous ecological ramifications). The persistence of non-native populations due to continual releases has a natural analogue in rescue effects, where populations in which deaths outnumber births can be maintained thanks to immigration into the region (Van Schmidt and Beissinger 2020). Secondly, understanding whether populations are likely to become self-sustaining will allow us to predict invasion likelihood. For example, certain species such as the Black Swan Cygnus atratus are potentially future naturalised components of the UK’s fauna. The extent to which such species currently have connected, self-sustaining populations is unclear. Studies assessing whether populations are likely to become ‘self-sustaining’ are likely to be of interest even outside of invasion biology, including with respect to reintroduced native species as well as endangered native species which have recovered demographically, but which appear to be dependent on continual human management (such as the Pink Pigeon Nesoenas mayeri of Mauritius (Edmunds et al. 2008)).

Concluding remarks

The Golden Pheasant appeared to be well-established in Britain during the mid-twentieth century. Its decline to inevitable extinction in recent years shows that introduced species can fail to maintain a presence in the long term, even if they initially appear to colonise successfully. There is a taxonomically and geographically broad range of species where considerations of their self-sustaining nature are of ecological and economic relevance. A thorough understanding of breeding success, juvenile dispersal, adult survival, and connectivity between subpopulations is needed to accurately determine the prospects of novel introduced species. In many cases where numbers are small, or ongoing introductions are suspected to be happening, further studies, including population viability analysis and studies of connectivity among different populations, will be needed to make informed decisions.

Data availability

This manuscript has no additional associated data.

References

Balmer DE, Browne SJ, Rehfisch MM (1996) A year in the life of golden pheasants. The introduction and naturalisation of birds. The Stationary Office, London

Birds of Poole Harbour (2020) Species list—Golden Pheasant [Online]. https://www.birdsofpooleharbour.co.uk/birds/. Accessed 28 Oct 2022

Birdtrack (2022) British trust for ornithology. Thetford, Norfolk, UK. https://www.bto.org/our-science/projects/birdtrack. Accessed 28 Oct 2022

Blackburn TM, Gaston KJ (2021) Contribution of non-native galliforms to annual variation in biomass of British birds. Biol Invasions 23:1549–1562

Brown AF, Grice PV (2005) Birds in England. T & A D Poyser, London

Clark JM, Eyre JA (1993) Birds of Hampshire. Hampshire Ornithological Society, Hampshire

Dudley SP (2005) Changes to category C of the British list†. Ibis 147:803–820

Eaton M, Baker H, Balmer D, Francis I, Holling M, King A, Norman D, Stanbury A, Stroud D (2021) Rare breeding birds in the UK in 2019. Br Birds 114:646–704

Eaton M, Baker H, Balmer D, Francis I, Holling M, King A, Norman D, Stanbury A, Stroud D (2022) Rare breeding birds in the UK in 2020. Br Birds 115:623–686

Ebird (2022) Cornell lab of ornithology, Ithaca, New York. http://www.ebird.org. Accessed 28 Oct 2022

Edmunds K, Bunbury N, Sawmy S, Jones CG, Bell DJ (2008) Restoring avian island endemics: use of supplementary food by the endangered Pink Pigeon (Columba mayeri). Emu-Austral Ornithol 108:74–80

Eyre J (ed) (2015) Hampshire bird atlas 2007–2012. Hampshire Ornithological Society, Hampshire

Gibbons DW, Reid JB, Chapman RA (1993) The new atlas of breeding birds in Britain and Ireland: 1988–1991. T. & A.D. Poyser, London

Holling M, Eaton M, Balmer D, Francis I, King A, Norman D, Stroud D (2017) Non-native breeding birds in the UK, 2012–2014. Br Birds 110:92–108

Holling M, Eaton M, Baker H, Balmer D, Francis I, King A, Norman D, Stroud D (2019) Rare breeding birds in the UK in 2017. Br Birds 112:706–758

Holling M, Eaton M, Baker H, Balmer D, Francis I, King A, Norman D, Stanbury A, Stroud D (2020) Rare breeding birds in the UK in 2018. Br Birds 113:737–791

Jeschke JM (2014) General hypotheses in invasion ecology. Divers Distrib 20:1229–1234

Joss A, Bain D, Clarke J, Etheridge B, Galloway D, Gordon P, Insley H, McMillan B, McNee A (2020) Highland bird report 2019

Joss A, Bain D, Clarke J, Etheridge B, Galloway D, Gordon P, Insley H, McMillan B, McNee A (2021) Highland bird report 2020

Lever C (2010) Naturalised birds of the world. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Lovegrove R, Williams G, Williams I (1994) Birds in wales. Poyser, London

McInerny CJ, Crochet P-A, Dudley SP, Bourc, Aerc (2022a) Assessing vagrants from translocated populations and defining self-sustaining populations of non-native, naturalized and translocated avian species. Ibis 164:924–928

McInerny CJ, Musgrove AJ, Gilroy JJ, Dudley SP, The British Ornithologists’ Union Records, C (2022b) The British list: a checklist of birds of Britain. Ibis 164:860–910

Nightingale B (2005) The status of Lady Amherst’s Pheasant in Britain. Br Birds 98:20–25

Parkin D, Knox A (2010) The status of birds in Britain and Ireland. A&C Black, London

Peng M-S, Wu F, Murphy RW, Yang X-J, Zhang Y-P (2016) An ancient record of an avian hybrid and the potential uses of art in ecology and conservation. Ibis 158:444–445

Sharrock JTR (1976) The atlas of breeding birds in Britain and Ireland. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford

Stoddart A (ed) (2022) Norfolk bird and mammal report 2021. Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists’ Society, Norwich

Taylor M, Marchant JH (2011) The Norfolk bird atlas: summer and winter distributions 1999–2007. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford

Taylor M, Allard P, Seago M, Dorling D (1999) The birds of Norfolk. Pica, Robertsbridge

Thom VM (2010) Birds in Scotland. Bloomsbury Publishing

Thomas A (ed) (2014) The birds of Sussex. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford

Twigg GI (1992) The black rat Rattus rattus in the United Kingdom in 1989. Mammal Rev 22:33–42

Van Schmidt ND, Beissinger SR (2020) The rescue effect and inference from isolation–extinction relationships. Ecol Lett 23:598–606

Wearing M (2011) The decline and fall of the Golden Pheasant (in East Hampshire). Kingfisher, Bury St Edmunds

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork and trapping was carried out under British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) ringing permits, with special permission from the BTO to target Golden Pheasants (a species that is not routinely ringed in Europe). This work would not have been possible without the landowners and staff who allowed access to their land to survey the Golden Pheasants, the numerous birdwatchers who shared their knowledge regarding the species and its status in various regions around the UK, and Ian Smith for logistical support with fieldwork. We would like to acknowledge Suffolk Bird Group, for providing funding to facilitate 2023 fieldwork, as well as Joe Woodman, Mark Rehfisch, and Alastair Stevenson for provision of photographs. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers, whose comments improved this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Suffolk Bird Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WJS conceived and designed the study with input from DEB and MTJ. WJS and MTJ carried out fieldwork. WJS wrote the manuscript and all authors commented on previous versions, before reading and approving the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, W.J., Jezierski, M.T. & Balmer, D.E. Discerning the status of a rapidly declining naturalised bird: the Golden Pheasant in Britain. Biol Invasions 25, 3341–3351 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03125-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03125-0